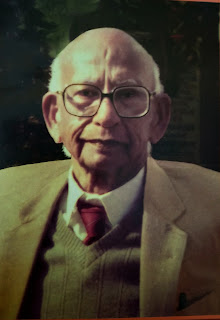

T.

S. Swaminathan (1909-2007)

Today,

June 25th, is my Father’s birthday. For me every day is Father’s

Day. I miss him today more than ever. Chocolates and cashew nuts were the only

gifts he would accept. Endowed with super encyclopaedical memory he could quote

from Sanskrit, Tamil and English literature. He dedicated his youth to his country and later

to his work. A devout follower of Sanatana dharma, his day began with chanting

Vishnu Sahasranamam. Our summer holidays were road trips to Thanjavur, museums

and temples. In his younger days, he mastered chess and photography. He built a

dark room in our bungalow for his equipment to develop film.

One

of the first Actuaries in India, he was instrumental in establishing Life

Insurance Corporation in 1955, and later after retirement was re-commissioned as

Chief Custodian for the formation of General Insurance Corporation. After he

retired for the second time, he was employed for 28 years in a company which

had overseas dealings. He studied the U.S. Law as their Legal and Financial

Advisor. He was 95 years old when he stopped working at this 9 to 5 job.

But

what his colleagues and officers will remember about him is his strong

incorruptible character and as a fearless votary of Truth. I found among my

papers this interesting jotting describing in his own words, his involvement in

the freedom movement.

Freedom Movement in Delhi 1930-1931

Delhi

in 1929, was surcharged with nationalist sentiment. I was in Delhi in June that

year in search of temporary employment. I was preparing for the ICS competitive

examinations two years later. Bhagat Singh and his friends were in the Lahore

Borstal jail. The sensational news of the uprising was constantly in the newspapers

and with the launching of the Salt Satyagraha movement in 1930, it became

impossible for me to complete a career as a government servant. I gave up the

goal of becoming an ICS Officer. I also felt that one could not keep oneself

away from this movement. Failure to participate in the national struggle cannot

be explained away. I became a part of the national movement but without any

official position therein. As soon as the Salt Satyagraha was announced, boycott

of foreign cloth, became an important part of the programme. Delhi at that time

was one of the most important cloth markets of Northern India, the other

centres being Amritsar and Kanpur. At Delhi I was having my residence in the

New Cloth Market on the Queen’s Road near the railway station-and more

important, close to the Company Bagh, where all political meetings were being

held. The boycott was very systematically organised in Delhi. We knew all the

places- Katra, Kusha and godowns where there were stocks of foreign cloth.

Volunteer guards were posted at all such places; any attempt to move the cloth

out of Katra or godowns resulted in slogan shouting by the volunteers and the resulting

crowd of Congress sympathizers effectively prevented any movement.

The

volunteers were there day and night. Unofficially, I used to take one or two

rounds every night to all these centres- all in Chandni Chowk. I was just

brushed aside and left with a bleeding injured foot. This attracted the

attention of the Press and the local leaders.

My

nocturnal rounds to the Katra and godowns became generally known. This system

was so effective that for nearly four or five months there was no movement of

foreign cloth.

The

Delhi merchants became desperate and some decided to brave the odium of the

shouts of “toady bachcha hai hai” and defy the boycott. One fine morning in

October 1930 there was a truck standing right in front of my residence in the

cloth market loading cloth from the opposite shop. I started shouting and tried

to stop the truck; the police took me into custody and charged me under the

picketing ordinance. The effect of my arrest on my immediate circle of friends

was electric. Two of my friends followed me into the jail by attending and trying

to address a banned public meeting.

Others were meeting us daily at the jail gate and giving us news.

I

was sentenced to six months rigorous imprisonment placed in ‘B’ Class and

transferred to the new Central Jail in Multan (now in Pakistan). In those days

all state level leaders were in Multan and the rest in Attock. At Multan the

“B” class prisoners consisted of representatives of all districts of Punjab.

From

Lyallpur and Sargodha Montgomery to Hissar and Rohtak, as well as had been

transferred with me from Delhi.

Life

in Multan in winter was bearable because of the company. The ‘B’ Class

prisoners formed a jolly good group as they were allowed rations and convict

servants to cook food. There was no real hardship. We held a mock round table

conference in the barrack.

However,

I was attracted by the idea of further sacrifice when I found that a very

respected leader Sardar Amar Singh Jhalbal and one Dandi marcher Krishnan Nair

were in ‘C’ class in the same jail. I

obtained a voluntary transfer to ‘C’ class. Here, life was more tough; very

rough blankets and shirts and bad food. No vegetables except radish and turnip.

I sustained myself on bad rotis and gur in lieu of cigarettes as remuneration

from the work done in the jail. But I had good company and I was able to

improve my knowledge of Urdu by having Premchand’s short stories (some volumes

were in circulation in the barracks) read out and explained to me. I formed

some friendships which continued even after the release from the jail. Amongst those in the jail were Batukeshwar

Dutt -a co-accused with Bhagat Singh in the Lahore Conspiracy Case, Chaudhary

Sher Jung -a scion of the princely house of Nahan (Sirmaurr)-turned-revolutionary

and Kharag Bahadur Singh, a Nepali inmate of Sabarmati Ashram who was a Dandi

marcher.

The

release from jail in March 1931, was a wonderful experience. We were welcomed

everywhere. I was travelling to Delhi with Kharag Bahadur Singh who was travelling

to Rohtak (about thirty miles from Delhi).

The

local public insisted that I too must get down at Rohtak. We were then taken in

procession through the streets of Rohtak.

After

his release from Multan Jail, one of my friends visited me in Delhi and we

spent a few days together discussing the future course of action. Revolutionary

activity was not excluded. Unfortunately, this was not to be. A bomb that he

was carrying exploded killing my friend Chand Singh instantly. The Police found

my address in Delhi among his personal effects. A police constable arrived in

my office at Chandni Chowk- about a hundred yards from the Kotwali- to summon

me for interrogation. Word got round that I had been arrested and there was

consternation in the office. My Gujarati boss sent me on a round tour of the

branch offices in Gujarat and Andhra to escape from the unwelcome attention of

the Police. I returned to the office in Delhi after five months.